The Stages of Audiation

An Overview

This is episode 5 of the Helping Children Audiate Music podcast. I’m Eric Bluestine and this episode is called The Stages of Audiation: An Overview.

I’ve used the word audiation several times in previous episodes of this podcast. And I think that, before I go any further into other topics, I should talk about audiation in some detail. Edwin Gordon coined the term audiation in 1975. In his early writings from that time, the term audiation appeared in a footnote, with a few sentences defining it. By the time Dr. Gordon wrote the final revision of his textbook Learning Sequences in Music in 2012, his thinking about audiation had greatly expanded. So now we have, officially, 6 stages and 8 types of audiation.

Here is the way Dr. Gordon, in 2012, defined the term audiation:

“Hearing and comprehending in one’s mind [the] sound of music [that is] not, or may never have been, physically present.”

(For clarity, I inserted the words “the” and “that is.”) This definition stresses the point that sound in our minds is not physically present because the sound we are processing has already become part of the past. For me, a more important point about audiation is that the music in our minds does not proceed at performance speed because we audiate only essential pitches and durations. But I’ll talk more about that in future podcast episodes.

If I were pressed to define audiation, I would say:

Audiation is the process of mentally organizing musical sound so that we understand how pieces of music develop.

This is a pretty good definition, but it’s incomplete because audiation is a process – and you can’t define a process, because a process by its very nature, won’t stand still! You can only explain what happens at each stage in the process.

Back in the summer of 1994, when I wrote my book The Ways Children Learn Music, I included a short chapter on audiation. Back then, I didn’t want the reader to get bogged down with too much detail about the stages and types. My goal was to explain, early in the book, what audiation is and what it’s not. (It’s not inner hearing. It’s not aural imagery. It’s not aural memorization. And so on.) I was then free to use the word audiation throughout the rest of the book because I knew that the reader knew basically what it meant.

That was 31 years ago. Since that time, I’ve been thinking that there may be a 7th stage of audiation. At the recent International GIML conference earlier this summer, I made a case for that 7th stage. And I’m hoping that with this podcast, I can make the case to a wider audience.

The challenge is that before I talk about a 7th stage of audiation, I need to bring everyone who’s listening up to speed about the 6 stages we already have. In this episode, I want to take you through all the stages rather quickly, so that, in future episodes, I can loop back around to each stage in more detail.

Back when I wrote my book, I talked about audiation by linking it with Star Trek and Leonard Nimoy’s character Mr. Spock, which, of course, made perfect sense. (It still does.)

Nowadays, I think the best way to talk about the stages of audiation is to talk about Orson Wells.

Now, if you’ve never heard of Orson Wells, please pause this episode, Google him, and then come back. And I’ll still be right here. You won’t miss a thing.

Anyway, if you are an Orson Welles fan—like I am—you won’t want to miss a fascinating radio program called Theatre of the Imagination – History of the Mercury Theatre on the Air. During the program, actress Geraldine Fitzgerald describes the stormy relationship between Orson Welles and his collaborator John Houseman. Back in the 1930s and 40s, Welles was an undisciplined creative genius, whose ideas were like water from a busted water main that gushes all over the street; Houseman was the disciplined collaborator with the thankless job of chasing after the water with buckets. I’ll stop there and let Geraldine Fitzgerald tell it better.

The uneasy truce between Welles and Houseman is a metaphor for what these podcast episodes on audiation will be about: the rivalry between musical form and fluidity.

On the surface, the next several episodes will be about Gordon’s Stages of Audiation, one episode for each stage. But more deeply, the episodes will cover the following topics: musical order and conflict; form and fluidity; ambiguity within and between musical elements; the elusiveness of clock-time; and the pecking order of essential pitches, durations, and musical patterns.

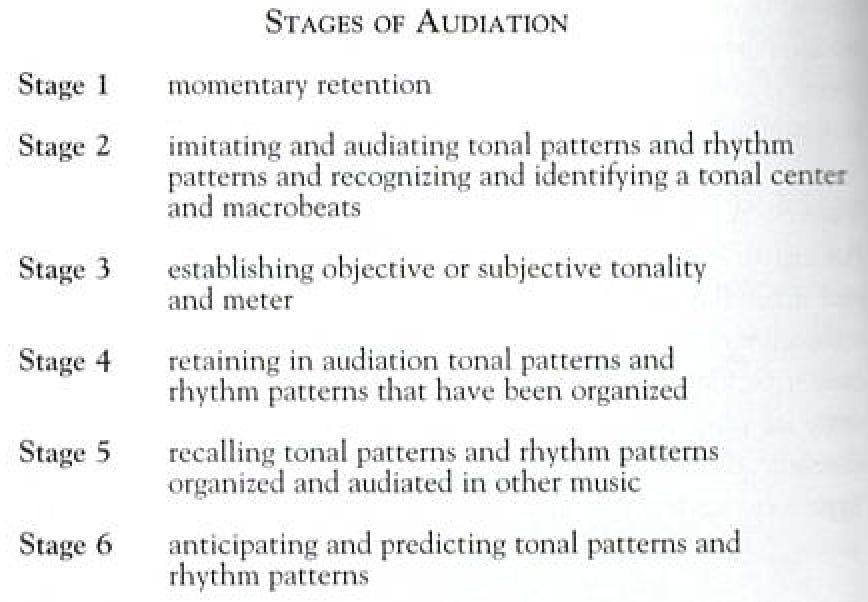

And now I’ll present Dr Gordon’s description of each of the stages. And by the way, I posted these description on Substack in the notes at the bottom of this episode, so you can follow along.

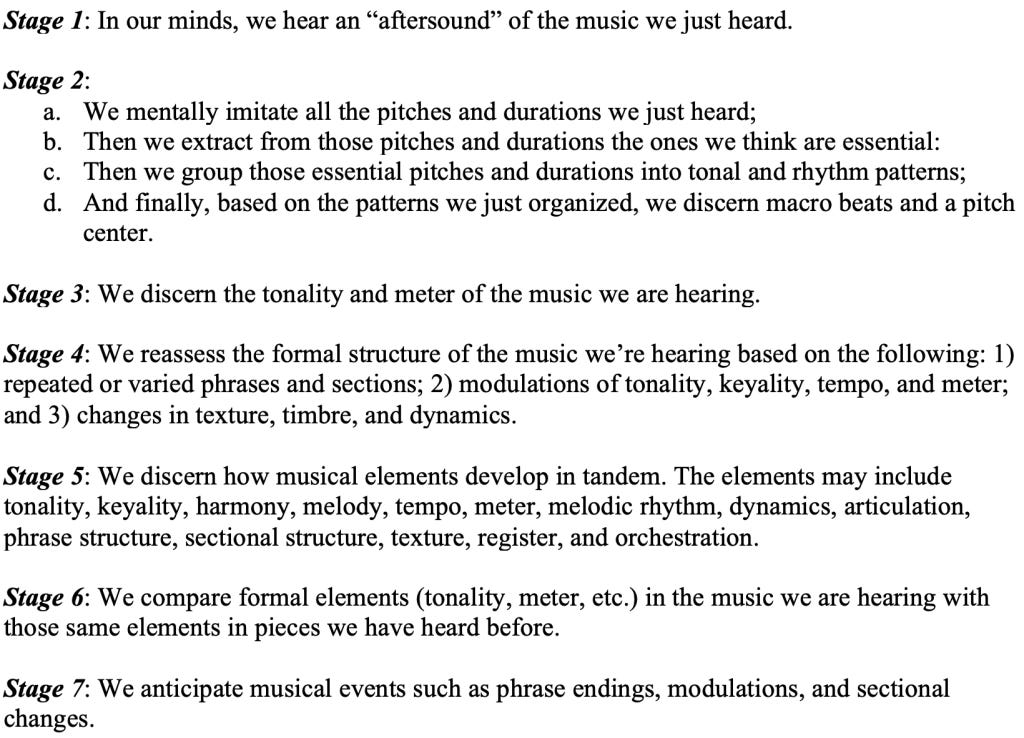

Now, that’s mouthful. I describe each stage a bit differently. But you’ll notice in my descriptions that I keep Dr. Gordon’s main ideas intact. Here is how I describe each stage of audiation, all 7 of them.

Yes, 7.

Making its way into the world is a new stage of audiation! I place it right after Gordon’s Stage 4. You’ll hear me talk about it as stage 5.

Here is how I describe each stage. And again, I posted my description on Substack in the notes at the bottom of this episode, so you can follow along.

That’s a lot to take in, and a lot to think about! There’s just no way to make these stages easy to absorb in just a few sentences. Even so, I tried to give each stage some breathing room. For instance, Gordon’s Stage 2 is, as I said earlier, really 4 sub-stages crammed into 1. I expanded it to make it the spacious, elegant creature you see in the notes at the bottom of this episode.

Also, I tried to flesh out ideas that Dr. Gordon touched on in his other writings. For instance, Gordon described stage 4 as mainly being about “retaining patterns.” But as I see it, Stage 4 is about vital things like form, modulation, and variation.

If you look broadly at how I described each stage, you’ll see I kept many of Gordon’s verbs: hear, imitate, anticipate, predict. I chose not to keep the verbs recall and retain because I think they’re self-evident. And I rejected outright the verb establish, which carries with it an arrogance I feel sure Gordon did not intend. When Bach composed — I’ll choose a piece at random — the Air from his French Suite in c minor, he, and he alone, “established” that this portion of the movement would begin in minor tonality and modulate to major. Such a decision, I believe, is within the purview of the composer only. As you listen to the piece now and audiate it, you, the listener, don’t establish that it modulates; you discern that it modulates.

Some listeners may be asking, is it not sacrilegious to rewrite Gordon’s stages, to say nothing of adding a new stage? In my view, it’s not sacrilegious at all. Gordon codified these stages; he did not invent them. They’re as old as music itself. “But they’re still Gordon’s stages!” I hear some of you insisting. All I can say is, if you who are hearing this episode want to challenge my changes, or add insight to them — especially if your comments are provocative, and contentious — then, I welcome your thoughts. And I will give you full credit for them!

Finally, why is it so important to look at these stages, to take them apart and reassemble them? Because they’re too important to gloss over, as I think many music teachers do, when they get bogged down with the pressure of teaching. These stages are about how music students learn to understand music; and by extension, they guide us in how we think and teach.

Please leave a message to let me know your thoughts on this topic. And thank you for listening.

Bluestine, Eric. 1995. The ways children learn music: An introduction and practical guide to music learning theory, 1st edition. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, Edwin. 2012. Learning Sequences in Music: Skill, Content, and Patterns. Chicago: GIA.

Maltin, Leonard. 2016. Theatre of the Imagination – History of the Mercury Theatre on the Air – Youtube, uploaded by Marc Baroni, 8 Sept. 2016,