The Stages of Audiation—An Overview

. . . But then begins a journey in my head . . .

—William Shakespeare, Sonnet 27

Introduction

If you’re an Orson Welles fan—like I am—you won’t want to miss a fascinating radio program called Theatre of the Imagination – History of the Mercury Theatre on the Air (Maltin, 2016). During the program, actress Geraldine Fitzgerald describes the stormy relationship between Orson Welles and his collaborator John Houseman. Back in the 1930s and 40s, Welles was an undisciplined creative genius, whose ideas were like water from a busted water main that gushes all over the street; Houseman was the disciplined collaborator with the thankless job of chasing after the water with buckets. . . I’ll stop there and let Geraldine Fitzgerald tell it better:

Geraldine Fitzgerald describing the Welles/Houseman relationship

This post is the first in a new series in which I’ll write about the stages of audiation. The uneasy truce between Welles and Houseman is a metaphor for what the series of posts will be about: the rivalry between musical form and fluidity.

On the surface, the next several posts will be about Gordon’s Stages of Audiation (2012), one post for each stage. More deeply, the posts will cover topics Gordon only touched on. You will read about the following: musical order and conflict; form and fluidity; ambiguity within and between musical elements; the elusiveness of clock-time; and the pecking order of essential pitches, durations, and musical patterns. And you’ll notice I’ve conspicuously added another stage! (Spoiler: Further down in this post, in FIGURE 2, you’ll see it as the new Stage 5.)

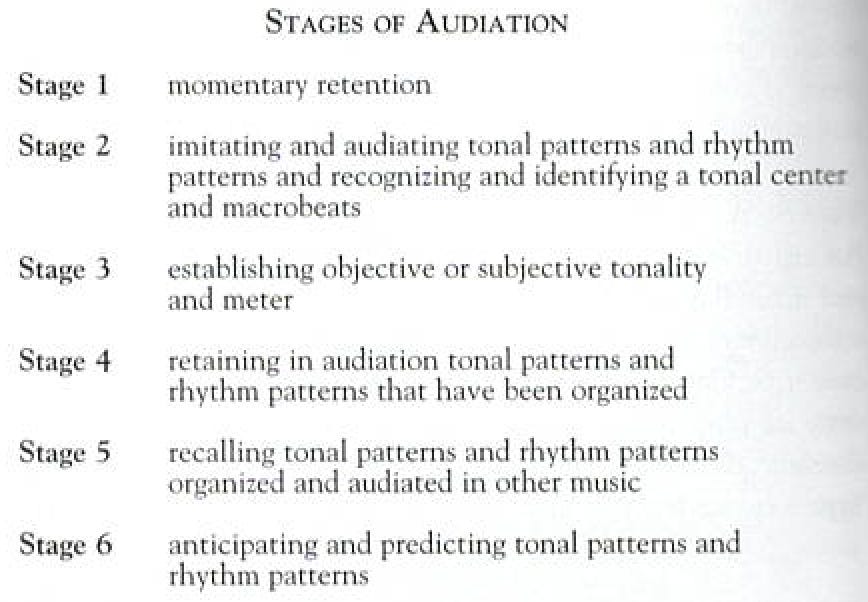

In FIGURE 1, you can see the stages of audiation as they appear in Dr. Gordon’s text (2012).

FIGURE 1: Gordon’s Stages of Audiation (Gordon, 2012)

In FIGURE 2 below, I present the stages a bit differently, but I still keep their main ideas intact. Here are my descriptions of each stage of audiation, all 7 of them.

Yes, 7.

Making its way into the world is a new stage of audiation! You’ll see it below as Stage 5.

FIGURE 2: My Summary of the Stages of Audiation

Let me say a few words about how I went about rewriting Gordon’s descriptions of each stage.

First, is it sacrilegious even to do so? Not at all. Gordon codified these stages; he did not invent them. They’re as old as music itself. “But they’re still Gordon’s stages!” I hear some of you insisting. My answer is, yes and no. It depends on how you look at the issue of rewriting. My view on the matter is as follows: Rewriting Gordon’s descriptions of the stages, but keeping his main ideas, was fairly easy to do. Adding my own ideas was much tougher; I really had to think things through. And let me say, up front, that I’m not done thinking. If you who are reading this post want to add insight to my changes—especially if your comments are provocative, challenging, and contentious—I welcome your thoughts. And I will give you full credit for them!

Second, Gordon wrote for an academic audience; but my audience—rank-and-file music teachers—may find his wording bookish and weighty. All those -ing verbs make the descriptions hard to digest. I tried to give each stage more breathing room. For instance, Gordon’s Stage 2 is really 4 stages crammed into 1. I expanded it to make it the spacious, elegant creature you see in FIGURE 2.

Third, Gordon sometimes stressed unimportant ideas, in my opinion, and buried crucial ones. For instance, Stage 4 is about vital things like form, modulation, and variation. Only incidentally is it about “retaining patterns.”

And now, we’re almost ready to tackle these stages one by one. You can find the post about Stage 1 here.

You can glean two broad points from this post: In our minds, music moves 1) at various rates of speed, and 2) backward and forward in time. The music we audiate does not proceed at the same rate of speed as it does in performance. What’s more, we retain in our minds music we heard seconds, minutes, hours, years before. And we predict and anticipate future musical happenings, even if we’ve never heard the music before.

Simply put, our musical minds are not locked into inexorable, second-by-second clock time; and when we mistakenly believe our minds are restricted this way, we end up sounding ridiculous.

Back in the mid-1980s at Temple University, I took my first general music methods class. I’ll never forget that the professor—who loathed MLT, and whose name I will not mention—made us write lesson plans according to a script, which included, as a course requirement, that we end every objective with the tag-line “as the music moves forward in time.” And so, despite how idiotic we were made to sound, we wrote objectives like these:

—Students will be able to perform a steady beat while they sing “Skip To My Lou” as the music moves forward in time.

—Students will be able to perform an ostinato on percussion instruments while they sing “Sandy Land” as the music moves forward in time.

I wouldn’t have minded attaching this phrase if it made sense; but in light of how we audiate, it’s complete nonsense. Music does not move “forward in time” only, but it also moves backward, taking us back to musical moments we heard seconds, minutes, even years before. And the “forward in time” sentiment leaves me believing that music proceeds at performance speed. But no. In our minds, we can slow the music down or zoom ahead, predicting what may happen in the music long before we hear it acoustically.

If you look closely at FIGURE 2, you’ll see I kept many of Gordon’s verbs: hear, imitate, anticipate, predict. I chose not to keep the verbs recall and retain because I think they’re self-evident. And I rejected outright the verb establish, which carries with it an arrogance I feel sure Gordon did not intend. When Bach composed — I’ll choose a piece at random — the Rondeau from his Orchestral Suite No.2, he, and he alone, “established” that the movement would be in minor tonality. Such a decision, I believe, is within the purview of the composer only. When you hear and audiate the excerpt below, you, the listener, don’t establish its tonality; you discern it.

Finally, why is it so important to look at these stages, to take them apart and reassemble them? Because they’re too important to gloss over, as I find myself doing so often when I read Gordon’s texts. They’re about how music students learn to understand music; and by extension, they guide us in how we think and teach.

Gordon, Edwin. 2012. Learning Sequences in Music: Skill, Content, and Patterns. Chicago: GIA.

Maltin, Leonard. 2016. Theatre of the Imagination – History of the Mercury Theatre on the Air – Youtube, uploaded by Marc Baroni, 8 Sept. 2016,